31 October, 2010

Day 114 - Battle of Britain

Officially, it's over. Today, after 114 days, the Battle of Britain formally ends. For the fliers, it is the quietest day for four months.

A few bombs are splattered over East Anglia and Scotland but neither side loses any aircraft in combat. The RAF loses a Beaufighter in a landing accident and the Germans lose two Do 17s in non-combat incidents.

This one time, even the night is quiet. The "raiders passed" siren sounds at the earliest time since September. People in shelters look at each other "almost in disbelief". But, warns the Daily Mirror, in a front-page headline the next morning: "Don't think air war is over". Curiously absent are the headlines declaring that the Battle of Britain is over - or even any sense that a turning point has been reached.

To inject a note of reality, the government issues an edict that the closing hour for shops through the winter — from 17 November to 2 March - will be 6pm, with an extension to 7.30 one night a week. That is the effect of a defence regulation, similar to that which was in force the previous winter. That much, at least, has changed.

That is one of the very few things that does change. The Mirror's warning is well made. Overnight on 1 November, heavy raids on London and a number of other towns and cities resume. Göbbels remarks in his diary that "Churchill invents a new lie about a massive attack on Berlin that never actually took place. Things must be very bad for him", he says. And the next day, and the days after than, it is bombing just the same.

Despite this, whatever the definition of the battle, and the time frame, it is indisputable that the Germans eventually lost. But could the Germans have ever won? That is a question posed by Lt Col Earle Lund, USAF, who carries out a Campaign Analysis Study in January 1996.

Lund asserts that the Luftwaffe at least twice, held victory in hand, yet failed to gain that victory. The point is simply this, he writes: all efforts should have been directly linked to the primary objective, which in both cases they were not. As proponents of Clauswitzian-style theory, and purveyors of the Principles of War - even of Douhet - the Luftwaffe failed miserably in the application of air warfare.

We are cautioned to bear in mind, though, that major air operations against Britain were discontinued not because they were recognized as hopeless or because they could no longer be justified in terms of the losses incurred. They ceased "by order of top-level command because the German Air Force was needed for the forthcoming war with Soviet Russia." In the final analysis, Lund asserts that the Germans could have won. Perhaps, if they had aggressively pursued either campaign strategy they could have won, he says, adding the rather obvious caveat that this "will always remain conjecture".

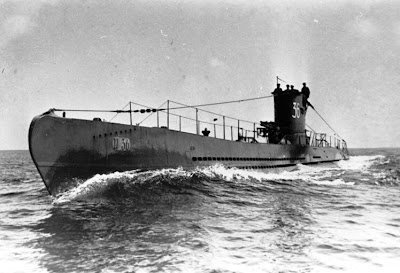

Therein though, lies the bigger story. As we saw only a few weeks ago Hitler's campaign against Russia was intended to serve many purposes, not least further isolating and cowing England - and thus helping to keep the US out of the war. After a swift victory, the bombers could return in force in the autumn of 1941. And in the meantime, out in the Atlantic, the U-Boats waited, augmented by the dreaded FW Condors.

In the autumn of 1940, therefore, the battle was far from over. It was to continue into the Spring of 1941 and then only the air component was put on hold while the Soviets were fought. That the campaign against the Soviet Union faltered on the outskirts of Moscow and then to become bogged down and founder in the cauldron of Stalingrad is perhaps the real reason why the Battle of Britain was finally lost by the Germans.

Hitler's fantasy, largely supported by his Generals, was that the Soviet Union could be conquered within six months. Had that happened, there is every reason to believe that, come the winter of 1941, the Luftwaffe air fleets would again have been camped in northern Europe, resuming the nightly blitz against London and other British cities. With the Soviet Union then out of the war, and the United States still sitting on the margins, who is to say that Britain would have resisted the renewed onslaught?

What then of the Battle of Britain? Beyond the hype and the rose-tinted spectacles, it really does have to be said that the short period of the daylight air fighting through mid-August to early September, was a strategic irrelevance. The much-vaunted "defeat" of the Luftwaffe on 15 September, celebrated as Battle of Britain day, was thus far from being the victory which it is so often portrayed. For sure, it was a reverse, but the effect was to enforce a change of policy, from day to night bombing - which was happening anyway. But from then, until the end of the Blitz in May 1941, far more damage was done than had hitherto been achieved.

One then has to ask what was the strategic purpose of this activity. The answer for this phase of the battle is the same as for the early phase (or phases) - to take Britain out of the war, achieving a cessation of hostilities. Missing here is the word "defeat" in the sense of securing the overwhelming military victory of the type inflicted on France. All the evidence indicates that Hitler would have accepted a deal, which kept the UK as an unoccupied nation, with its Empire largely intact.

This, then, points to a much-neglected aspect of the Battle of Britain - the politics. Having pieced together some of what went on and looked at those events as part of an integral whole, the entire complexion of the Battle changes. Essentially, the first phase of the fighting, up to 13 August 1940, is simply skirmishing - the greater strength of the Luftwaffe being held back while various peace initiatives were pursued.

It was only in early August, when Churchill finally rejected the peace proposal brokered by the King of Sweden, that the full force of the Luftwaffe was finally committed. We then see an attack on the RAF, which actually has very little direct relevance to preparations for an invasion. The invasion is best seen as more threat than reality, alongside the air campaign, creating psychological pressure on Churchill and his government, in the hope of a moral rather than military collapse.

This, in the context, is far from unreasonable or illogical. The fall of France was engineered as much by moral dominance as military victory, and Hitler quite clearly had expectations of repeating the trick. And when the direct assault on the RAF - together with the "hype" about an impending invasion - failed to have a desired effect, the tactics were changed, and London was bombed.

Far from being a "mistake" as is commonly portrayed in the standard hagiographies, this was effectively a repeat of the earlier strategy, albeit on a more intense scale - an air assault followed by peace "feelers" in the expectation of a deal.

Here, although we lack clear documentation, there are unmistakable signs and extremely good evidence that peace initiatives recommenced in early September, alongside that start of the Blitz. There is, however, no clear evidence as to when these were concluded - as we see with the August rejection. Perhaps it continued into the Spring, culminating in the mysterious flight of Rudolf Hess in May 1941, about which even today there is much controversy.

The point in our narrative though is that we see three phases to the Battle of Britain. First, there was an intensification of the fighting through July, accompanied by a peace initiative, the two issues closely interwoven. Then we see an intensive air assault through August - this one in the expectation of a moral collapse of the British government. This was followed by phase three, the Blitz, again accompanied by a peace initiative(s), running through until May 1941. The air battles of phase four, to be commenced in the winter of 1941, never happened - although the background economic war continued in the form of the Battle of the Atlantic.

That we never had to suffer a renewed air assault of the intensity of the earlier Blitz is something for which we have to thank the Soviet Union. Its defence of its territory proved to be the saviour of Britain, and paved the way for the victory of the Allies in 1945. But the British contribution was to stay in the war. But that Battle did not last a mere 114 days. It ran from the fall of France to December 1941, when the first and most important strategic aim of the British was achieved. The United States joined the war.

COMMENT: Battle of Britain thread

30 October, 2010

Day 113 - Battle of Britain

"People need coal", says the leader in the Daily Express, on page 4. The front page headline is focused entirely on the war in Greece. The only reference to the Battle of Britain is a report on the appearance of the Italian Air Force in British skies.

Not even the growing ranks of the Air Ministry propaganda unit can give the air battle any higher profile. Fighter Command has disappeared, pro temp, from the script, and never again will it capture the headlines in the way it has done over the heady days of July through to September.

The reality of war is now upon people who are looking to their second winter of the conflict, dreading its onset. And well they might. The transport system is on the brink, and to make matters worse, trains are ordered to slow to 10mph through the innumerable air raids. The delays mean they are simply not delivering the coal. Despite the summer to replenish stocks, shortages of supply loom, replicating the winter before.

Thus complains the Express leader, "Mr Smith has no pile in his backyard, Mr Jones cannot order a ton and be sure of getting it. Again, we repeat. Risk is our normal lot. Safety must not impede speed. For we cannot be safe now, and we will not be safe ever unless we work at speed to throw off this great parasite of war that sucks at our happiness, our wealth, and our free will."

The great battles of the summer, with contrails criss-crossing the sky, are no more. Today, sullen October weather hampers flying. Only small numbers of Luftwaffe brave the rain and the autumnal gloom. Even the night raiders, who are used to flying in poor visibility, are discouraged by the poor weather.

In the public mind, the "few" is a distant memory, although operational intensity is as high as it has ever been (and higher than it was at the beginning of the battle) and they still are taking losses. An RAF fighter pilot's life is measured as 87 flying hours. Just today, the last day in which there are combat casualties, seven fighters are written off and three pilots are killed. Eight Luftwaffe aircraft are lost, including a Henschel 126 in a non-combat incident.

One RAF pilot is shot down over the Channel. He does not survive. A Me 109 pilot is also shot down over the Channel. He is rescued by Sennotflugkommando, unwounded. RAF Battle of Britain survivors eventually come to be lionised as "The Few". The Air Ministry's task, it seems, is to make sure there are as few of the few as possible.

Meanwhile several newspapers, without any great prominence, are publishing the latest figures for shipping losses. The week ended 20-21 October has been the blackest since the evacuation from Dunkirk. Britain has lost thirty-two ships, totalling 146,528 tons, Allied losses run to seven ships, totalling 24,686 tons, and six neutral ships totalling 26,816 tons are lost. The cumulative total is 198,939 tons,

We are told that Germany paid for her successes with U-boat losses, and that the Navy is increasing its precautions against U-boat attack, but there is no disguising the growing crisis. Despite this, there is no repeat of the Daily Mirror's sentiment from earlier in the month, even if here is writ large one important effect of the invasion threat. With so many patrol vessels kept in UK ports at immediate readiness, convoy escorts have been dangerously depleted.

Whether intended or not, Göring, his airmen, and the threat of invasion have assisted the blockade by drawing off resources which might otherwise have been used to protect shipping. Fighter Command may be taking the glory for the battle in the skies above Britain, but merchant seamen are paying the price.

COMMENT: Battle of Britain thread

29 October, 2010

Day 112 - Battle of Britain

The first day of the Italian invasion of Greece, and the heavy raids by Bomber Command on the Skoda works in Czechoslovakia, drove news of domestic air fighting from the front pages. Yet significant operations were continuing. Overnight, Birmingham had been heavily bombed again, with New Street Station badly damaged.

The War Cabinet was told that a number of German vessels had been reported in the Channel making eastwards. It was, however, too early to draw the deduction that the risk of invasion had receded. Some sixty good German divisions were ready at short notice, close to the invasion ports. So long as that situation continued, it would be essential for us to keep a number of divisions in readiness at home. Thus, the Minister of Information was invited to "inculcate the need for continued vigilance in our preparations against invasion".

As to the daylight air war, after early mist, raids had started mid-morning and carried on into the early evening. Four daylight raids on London and two on Portsmouth were recorded, the largest involving forty bombers escorted by Messerschmitt fighters. No. 602 City of Glasgow Sqn distinguished itself by shooting down eleven Me 109s in six minutes, for no loss.

Fifteen Italian BR 20s (type illustrated above), escorted by CR 42 biplanes, attacked Ramsgate. Five were damaged by anti-aircraft fire. At dusk, RAF airfields in East Anglia, Lincolnshire and Yorkshire were attacked by Ju 88s and Me 109s. Heavy night bombing of Birmingham and Coventry was recorded. London was again bombed.

On the day, Fighter Command lost ten aircraft, including two Hurricanes caught while taking off from North Weald Airfield during an attack. One pilot was killed there. But Bomber and Coastal Commands lost eight aircraft, including two Sunderland flying boats. The Germans lost twenty-four aircraft, including fifteen Me 109s.

COMMENT: Battle of Britain thread

28 October, 2010

Day 111 - Battle of Britain

Germany announces "European Front" against England. This is no mere polemic, but a carefully constructed propaganda campaign aimed at the United States, to position the United Kingdom as the "aggressor" against a united Europe. Only England's intransigence is causing the war to continue. Without her, and the warmonger Churchill, there would be peace.

It is the Daily Mirror, oddly enough, which picks up the vibes on Greece most prominently, splashing the Italian moves on its front page as the lead item. Initiated without consultation with the Germans, Hitler is said to be furious and an emergency meeting is arranged. It is too late to stop Mussolini, so a facade of unity is projected to the outside world. But it makes a mockery of Germany's propaganda play.

Too soon for the British press to report, the details on the moves on the ground are retailed by the New York Times. The Italian government had served an ultimatum at 03:00hrs, to expire at 06:00hrs. Italy was then reported to have attacked Greece by land, sea and air, "hurling" at least ten divisions of 20,000 troops across the Albanian-Greek border.

British sources declared that warships of the British Mediterranean Squadron were steaming from their patrol posts to the assistance of Greece, "who holds a British guarantee of aid in event of attack",

The Daily Express chooses to feature RAF raids on Berlin, claiming that the heaviest bombs ever have been dropped on the city in a "fierce" ninety-minute raid that "showed Berlin what blitz-bombing is really like". "Many works smashed, trams and buses wrecked, gas cut off", the sub-heading to the report reads. There is a small item about the Empress of Britain in the Mirror, the paper noting that the Nazis are saying that the ship is still on fire, having claimed two days ago on the Saturday that it had been sunk.

There is little more on Petain, with the Yorkshire Post noting that "this has been a week-end of waiting in London for further news" on the Hitler-Petain pact. Until further information on the terms of the pact, and on certain other questions, is available, it would be fruitless to speculate widely on what the agreement may involve, the paper says. It continues:

As the war goes on elsewhere, a haunting incident occurs far out in the Atlantic. Sunderland P9620 becomes lost while on convoy patrol after its compass fails in an electrical storm. The aircraft runs out of fuel and is forced to ditch, some 200 miles west of Ireland. It stays afloat for nine hours in gale conditions before breaking up. Of the 13-man crew, nine are rescued by HMAS Australia. In gathering darkness, a crewman is seen on the keel of the upturned craft as it drifts away into the gloom. He is not saved.

COMMENT: Battle of Britain thread

It is the Daily Mirror, oddly enough, which picks up the vibes on Greece most prominently, splashing the Italian moves on its front page as the lead item. Initiated without consultation with the Germans, Hitler is said to be furious and an emergency meeting is arranged. It is too late to stop Mussolini, so a facade of unity is projected to the outside world. But it makes a mockery of Germany's propaganda play.

Too soon for the British press to report, the details on the moves on the ground are retailed by the New York Times. The Italian government had served an ultimatum at 03:00hrs, to expire at 06:00hrs. Italy was then reported to have attacked Greece by land, sea and air, "hurling" at least ten divisions of 20,000 troops across the Albanian-Greek border.

British sources declared that warships of the British Mediterranean Squadron were steaming from their patrol posts to the assistance of Greece, "who holds a British guarantee of aid in event of attack",

The Daily Express chooses to feature RAF raids on Berlin, claiming that the heaviest bombs ever have been dropped on the city in a "fierce" ninety-minute raid that "showed Berlin what blitz-bombing is really like". "Many works smashed, trams and buses wrecked, gas cut off", the sub-heading to the report reads. There is a small item about the Empress of Britain in the Mirror, the paper noting that the Nazis are saying that the ship is still on fire, having claimed two days ago on the Saturday that it had been sunk.

There is little more on Petain, with the Yorkshire Post noting that "this has been a week-end of waiting in London for further news" on the Hitler-Petain pact. Until further information on the terms of the pact, and on certain other questions, is available, it would be fruitless to speculate widely on what the agreement may involve, the paper says. It continues:

It seems at least possible, however, that Petain is still trying to hold out against some of Hitler's demands. But the veteran leader of the Vichy Government has placed himself in an extremely difficult position with Hitler by his unconditional capitulation last summer. Petain may now feel that he is faced with only two possibilities: complete surrender to the Fuehrer or resistance which France is in no position to maintain.Back in Britain, night spotters of enemy aircraft assert that three-engined aeroplanes have been used for some of the attacks on London. This lends confirmation to the German report that the Regia Aeronautica has been in action against Britain. Very soon, there is the physical evidence.

As the war goes on elsewhere, a haunting incident occurs far out in the Atlantic. Sunderland P9620 becomes lost while on convoy patrol after its compass fails in an electrical storm. The aircraft runs out of fuel and is forced to ditch, some 200 miles west of Ireland. It stays afloat for nine hours in gale conditions before breaking up. Of the 13-man crew, nine are rescued by HMAS Australia. In gathering darkness, a crewman is seen on the keel of the upturned craft as it drifts away into the gloom. He is not saved.

COMMENT: Battle of Britain thread

27 October, 2010

Day 110 - Battle of Britain

The long-running Petain saga seems to be coming to a close, with the word "collaboration" high up in the lists of comment. France, somewhat under force majeure, is to integrate politically and economically with Germany, as part of the Nazi's idea of a new world order. However, Petain seems to have avoided full military integration, with a declaration of war against Great Britain. It is still a hostile power, but not a belligerent. The United States threatens to seize French overseas possessions if military co-operation between Vichy and Germany is too close.

In the same edition of the Observer, where we see the news on France, there is also news of the Empress of Britain. German radio has declared her sunk. This is premature as, even as the paper rolls of the presses, a heroic struggle is under way to get the ship into port. The coup de grace comes not until tomorrow. The New York Times, on the other hand, has the ship on fire and beyond salvage.

This day, a German radio message is picked up by a radio listening post in Britain. Deciphered by the top-secret facility at Bletchley, and included in the "Ultra" intercepts, it instructs German forces gathered at the invasion ports "to continue their training according to plan". This is interpreted as meaning that an invasion could hardly be imminent, if training was to continue. Churchill is informed of the intercept and the conclusion.

The next day, photographic reconnaissance picks up substantial movement of shipping out of the invasion ports. It is moving eastwards, away from Great Britain. By 2 November, Churchill's private secretary is writing in his diary that the prime minister "now thinks the invasion is off".

Meanwhile, tension between the Greeks and the Italians who are camped in Albania along the Greek border, are increasing. Late in the evening, Italian ambassador in Athens Emanuele Grazzi relays an ultimatum from Mussolini. It demands that Italian troops be allowed occupy strategic points in Greece. Ioannis Metaxas, the Greek dictator, rejects the ultimatum, noting "Alors, c'est la guerre". The Greeks know of the Italian plans and have already mobilised in the areas facing the expected attack.

COMMENT: Battle of Britain thread

26 October, 2010

Day 109 - Battle of Britain

There is no official or semi-official information as to the scope of the conversation between Hitler and Marshal Petain. A statement issued by the official German News Agency says: "Hitler did not hesitate to treat the Marshal as a great and honourable opponent deserved to be treated." That is the "take" from the Yorkshire Post. Others, like the Daily Mirror, hint at "surrender", and the Daily Express covers US intervention, aimed at stopping a Franco-German pact.

Noting Petain's discomfort, evidenced by the protracted negotiations, the Express cannot resist the temptation to moralise. "Now you see what it is like to be beaten. Look at France. Look at Petain creeping to the feet of the conqueror, asking what it is he wants," the paper storms. "As we watch each step of that dreadful and pitiful pilgrimage we sing anew the praises of our invincible Navy and our unbeatable Air Force".

Several newspapers focus on yet another gun duel across the Straits of Dover, the narrative running to a pattern established back in late August when the German shelling started. The German guns shell a convoy - unusually, German aircraft join in. The British guns respond. British bombers roar into action, launching the biggest raid yet on German-occupied France. Honour is satisfied. The warriors stand down, clean their guns and finish off the day with a late tea, or something stronger. Alan Brooke and others fret about the enormous expenditure of manpower on Winnie's "pets".

For the rest, it is déjà vu all over again. A small number of jabos and their escorts fly across the Channel and head towards London. Like the day before, and the day before that, and the day before that, some actually get to drop their bombs over the city. This time, the Royal Chelsea Hospital is hit.

The RAF flies 732 sorties, nine German aircraft are destroyed as are nine RAF fighters - by no means all, on either side, through combat damage. Two Hurricanes are lost on night take-offs, their pilots killed, and one Blenheim crashes on landing after a night sortie. The crew is unhurt. Additionally, two Beauforts, a Blenheim, two Hudsons, a Hampden and a Whitley are lost by Bomber and Coastal Commands. The FAA loses a Swordfish.

The big event though - not yet broadcast to the nation - is a Luftwaffe attack on the former liner and now troopship the Empress of Britain. She is found by a roving Condor about 150 miles from land, off the north-west coast of Ireland. Hptm. Bernard Jope, the aircraft captain, releases two bombs on the ship. He then strafes her, taking return fire from deck-mounted machine guns.

The bombs start large fires which soon cripple the ship. Many crew are trapped below deck by the fires, some forced to escape through portholes into the sea. A Sunderland and three Blenheims assist with the rescue. Under constant air cover from Hurricanes from No. 245 Sqn out of Aldergrove, the ship limps eastwards, only to be torpedoed by U-32 on 28 October while under tow.

Most of the 643 passengers and crew are taken off. Only 45 are killed, all passengers in the initial attack. At 42,348 grt, she is the largest liner to be sunk through the entire war. Jope is eventually to become a senior Captain with Lufthansa. U-32 is sunk by the destroyer Harvester, two days after she despatches the Empress.

Back in Britian, the creatures of the night are on the prowl again. They hit London and Birmingham heavily. New Street station in Birmingham is closed by an unexploded bomb. But for some, the war has become a spectator sport once more. The Daily Express reports thousands of people crowding Kent seafronts to watch and hear "terrific battles between convoys, planes and long range guns which shook the coast from early yesterday evening to long after dark," as German long-range guns, with the aid of a terrific bombing by the RAF, lit up the whole French coast between Calais and Boulogne.

COMMENT: Battle of Britain thread

25 October, 2010

Day 108 - Battle of Britain

The newspapers had little more to add to the Pétain affair than when they first reported the meeting with Hitler. The Yorkshire Post, however, rather stiffly informed its readers that Germany might be about to launch a monster propaganda campaign carrying falsification to lengths far exceeding those already attempted designed to show that Britain’s chances of withstanding German might were hopeless.

The Mirror announced a "Better night fighter plane". The paper, with others, was reporting on a BBC commentary the previous evening by Air Marshal Sir Philip Joubert. Amazingly, he was referring to the Defiant, saying that the aircraft, "originally designed as a night fighter and used experimentally for a while by day", had now been restored to its proper role and "with certain developments that we are considering, should be very effective". It wasn't. The aircraft was not suited to radar interception. That Joubert felt the need to talk up the Defiant simply reflected the growing unease at the inability of the RAF to deal with the night bomber, and its desperation to come up with a solution.

The claim was, to say the very least, disingenuous, both as to its original role and as to its future effectiveness. The aircraft was not suited to carrying interception radar and, although the Mk II model was fitted with the AI Mk IV, it was never really successful as a night interceptor. With the twin-engined Bristol Beaufighter already on the stocks, the aircraft was withdrawn from combat duties in 1942 and used only for target towing and sundry other non-combat tasks.

But even in the daytime, the RAF was finding it hard to keep the Luftwaffe

at bay. Three people were killed when a German fighter-bomber scored a direct

hit on trams in Blackfriars Road, London, during a daylight raid. The trams

worst hit were in the middle of a group of five, drawn up near traffic lights.

The dead included a driver, a conductor and a woman passenger. A number of

women ripped up their clothing to provide temporary bandages for the injured,

of which four had been taken to hospital. Many others were cut by flying glass.

Adjoining buildings were badly damaged.

Come the night, though, an even greater horror visited the Druid Street railway arch shelter in Bermondsey. The area under the arch was used as a social club and billiards hall during the day but, at night, it was transformed into a sanctuary from the bombing. The ominous sound of the sirens were the cue for local people to congregate as quickly as possible in a bid for safety. That night, it took a direct hit. Many were killed instantly and many died later of their injuries. The final death toll was 77. Censorship kept the details from the wider public.

And for for the first time, Italian aircraft were committed to an operation over British soil. Thirteen aircraft took part in a raid against Harwich.

COMMENT: Battle of Britain thread

The Mirror announced a "Better night fighter plane". The paper, with others, was reporting on a BBC commentary the previous evening by Air Marshal Sir Philip Joubert. Amazingly, he was referring to the Defiant, saying that the aircraft, "originally designed as a night fighter and used experimentally for a while by day", had now been restored to its proper role and "with certain developments that we are considering, should be very effective". It wasn't. The aircraft was not suited to radar interception. That Joubert felt the need to talk up the Defiant simply reflected the growing unease at the inability of the RAF to deal with the night bomber, and its desperation to come up with a solution.

The claim was, to say the very least, disingenuous, both as to its original role and as to its future effectiveness. The aircraft was not suited to carrying interception radar and, although the Mk II model was fitted with the AI Mk IV, it was never really successful as a night interceptor. With the twin-engined Bristol Beaufighter already on the stocks, the aircraft was withdrawn from combat duties in 1942 and used only for target towing and sundry other non-combat tasks.

Come the night, though, an even greater horror visited the Druid Street railway arch shelter in Bermondsey. The area under the arch was used as a social club and billiards hall during the day but, at night, it was transformed into a sanctuary from the bombing. The ominous sound of the sirens were the cue for local people to congregate as quickly as possible in a bid for safety. That night, it took a direct hit. Many were killed instantly and many died later of their injuries. The final death toll was 77. Censorship kept the details from the wider public.

And for for the first time, Italian aircraft were committed to an operation over British soil. Thirteen aircraft took part in a raid against Harwich.

COMMENT: Battle of Britain thread

24 October, 2010

Day 107 - Battle of Britain

A few individual raiders and reconnaissance flights is the extent of German daylight air operations. From a British perspective, this is seen to be a ritual to keep the British defence system on alert, with no strategic significance whatsoever. The main effort now is through the night.

Flight magazine has already made a decision about this. The Battle of Britain is over as a battle and has degenerated into unimportant but spiteful slaughter and destruction, it says. But, once again, it is focused on day operations and the fighter war.

This, however, is not the German "take" on the situation. General von Bötticher, the German Military Attache to Washington, reports that the situation in England is becoming more precarious. The objective to make life more difficult and to make life difficult is being achieved. Production has decreased and the traffic situation is difficult. There is a danger that epidemics might break out. Reports from the embassies in Lisbon and Sofia agree. There has been an "impressive change" in the tone of the British press.

On the British front, however, internal politics rather than the Germans are keeping Dowding busy. He has let the enmity between Keith Park at 11 Group and Leigh Mallory at 12 Group go too far. The knives are out, and Dowding's own position is threatened. But, while the headline issue is the so-called "big wing" controversy, the politicians are also dismayed at the lack of protection Fighter Command can offer against the night bombers. Heads must roll.

To prove the point, London gets 50 aircraft in the night. Birmingham is also a target while Basingstoke is also hit. The Luftwaffe roams virtually unmolested, still owning the night sky. The weather is the bigger enemy, accounting for more losses that the RAF on this day.

RAF politics, though, is trivial stuff, when the real thing is in plentiful supply. News is emerging of a meeting the previous day between Hitler and Franco on the border of Spain. During the Brenner meeting between Hitler and Mussolini, news had been circulating to the effect that Spain's dictator, Franco, had decided to stay out of the war. Now Hitler is trying to reverse that decision.

|

| Hitler meeting with General Francisco Franco at Hendaye, Southern France |

In a two-hour, head-to-head discussion, though, Hitler fails to change his mind. Famously, Hitler later confides with Mussolini that he would "rather have three or four teeth pulled" than go through another meeting with Franco. And so, Gibraltar is safe.

From the Spanish border, Hitler travels to Montoire in France to meet Petain. News has since come through that Petain has rejected any deal with Hitler over the transfer of the French Navy. However, the fleet is said to be massing in Toulon. The only explanation for this "mysterious move", is said to be that the French Navy minister, Admiral Darlan, who is a strong supporter of deputy premier Laval, gave the orders on his own initiative.

While the world waits with bated breath for news of developments, the War Cabinet is treated to a sombre appraisal on the current fighting. In particular, it learns that mines are having a significant effect on the shipping in coastal waters and on the Royal Navy in particular.

In the preceding week, they have accounted for the numerous ships. Minesweeper HMS Dundalk is badly damaged 16 October off Harwich and founders early the next day while under tow. HM Trawler Kingston Cairngorm is sunk off Portland on the 18th, and veteran of the action in Boulogne to evacuate troops, HM Destroyer Venetia (pictured below at Boulogne) goes down in the Thames Approaches on the 19th. There are 96 survivors from the latter ship, but five officers, including the Captain, are missing.

|

| HMS Venetia at Boulogne, 23 May 1940 |

HM Trawler Velia is also sunk in the same locality. The Minesweeping Trawlers Wave Flower and Joseph Button are sunk off Aldeburgh, apparently by mines, on the 21st and 22nd respectively, and HM Trawler Hickory sinks off Portland on the 22nd.

The picture for merchant shipping is no better. During the period, 36 ships (150,091 tons) have been reported sunk. Of these, 17 British (89,199 tons), three Norwegian (14,080 tons), three Swedish (13,533 tons), three Dutch (10,878 tons), two Greek (7,408 tons), one Estonian (1,186 tons), one Belgian (5,186 tons) and one Yugo-Slav (5,135 tons) were sunk by submarine.

Three British vessels (1,722 tons) were sunk by mine, one British (1,595 tons) was sunk by E-Boat and a British trawler (169 tons) was sunk by aircraft. In addition, three British ships (21,059 tons) previously reported as damaged were now known to have been sunk. Damage by aircraft, mine or submarine to 21 British ships (79,791 tons) had been reported and two additional British ships (10,232 tons) are now known to have been damaged in the previous period.

As to civilian casualties, the approximate figures for the week ending 06:00hrs on 23 October are 1,690 killed and 3,000 injured. These figures include the estimated 1,470 killed and 1,785 injured in London, 56 killed and and 261 injured in Coventry, and 30 killed and 203 injured in Birmingham.

But there is one thing few are concerned about - the invasion. Even the Lord Halifax is in the loop. On this day he notifies a British embassy that: "‘Though Hitler has enough shipping in the Channel to put half a million men onto salt water – or into it, as Winston said the other day –it really does seem as if the invasion of England has been postponed for the present".

’

COMMENT: Battle of Britain thread

23 October, 2010

Day 106 - Battle of Britain

Weather here good, wrote Goebbels in Berlin, bad over England."Few incursions into the Reich, but neither do we drop much in England". The propaganda minister is not far wrong. Low cloud and drizzle, with the concomitant poor visibility, prevents any significant German air operations, either by day or night.

The Luftwaffe reverts to its standard bad weather programme, sending out reconnaissance flights and single bomb-carrying fighters. One Hurricane is lost to an Me 109 and the Luftwaffe loses three bombers, two from the night contingent. Only one of the three is a direct combat loss - the other two crash on home territory.

The OKW War Diary this day records a report from London which states that the effects of the German attack on London and the British industry were not very strong during September. During October, however, the effects are said to have been stronger. "The British people is said to be fatalistic," it notes. "The people, however, does not appear demoralised".

Separately, in relation to the dispersion of forces intended for operation Seelöwe, it is recorded that: "long periods of time will, in future, be required to get this operation going". It then adds: "The measures to deceive the enemy are to be continued but the main effort of this deception should be directed to Norway".

The diary also carries a report on Luftwaffe operations. "The morale of the flying units is excellent", it says. "These units are strained but not over-strained." It then goes on to observe that, in general, only fighter-bomber aircraft equipped with 250Kg bombs are to be committed in daylight operations against London and alternate targets. These are to fly at extremely high altitudes and, it is thought, the damages caused in London are "very considerable".

In Britain, the media focus is not on the domestic front. Big events are being staged in France where, only 24 hours after Churchill has made a radio appeal to the French to rise up and set Europe aflame.

Predictably, Göbbels is less than impressed. "Impudent, insulting, and oozing with hypocrisy", he calls it, "A repulsive, oily obscenity". He releases the speech to the [German] press for them "to give it a really rough and ready answer" Otherwise, he writes, the English will carry on living an illusion. We shall battle on remorselessly to destroy their last hopes.

This day, Hitler arrives secretly in Paris to have a long conference with Pierre Laval. Reports emerging from Berlin indicate that Hitler is offering final peace terms to France in exchange for the surrender of the remnants of the French fleet. With the help of the French, Hitler and Mussolini are said to be planning a "decisive blow against the British Fleet in the Mediterranean.

According to the Daily Express, "Jubilant Nazi officials in Berlin boast that the three navies could either destroy the British Fleet or drive it off our great Empire lifeline."

Combat fliers were not the only casualties this day. On a scheduled flight to Belfast from RAF Hendon was a Hertfordshire aircraft, the militarised version of the De Haviland Flamingo passenger aircraft, and the only one of its kind. Shortly after take-off, its elevator jammed and it crashed at Mill Hill, a few miles north.

Eleven people were killed – five crew and six passengers, the latter including Air Vice Marshal Blount, a first-class cricketer and commander of the air component of the BEF in France. After the Battle of France, he had returned to England to resume his original post as AOC, No. 22 (Army Co-Operation) Group. He was three days short of his 47th birthday.

COMMENT: Battle of Britain thread

The Luftwaffe reverts to its standard bad weather programme, sending out reconnaissance flights and single bomb-carrying fighters. One Hurricane is lost to an Me 109 and the Luftwaffe loses three bombers, two from the night contingent. Only one of the three is a direct combat loss - the other two crash on home territory.

The OKW War Diary this day records a report from London which states that the effects of the German attack on London and the British industry were not very strong during September. During October, however, the effects are said to have been stronger. "The British people is said to be fatalistic," it notes. "The people, however, does not appear demoralised".

Separately, in relation to the dispersion of forces intended for operation Seelöwe, it is recorded that: "long periods of time will, in future, be required to get this operation going". It then adds: "The measures to deceive the enemy are to be continued but the main effort of this deception should be directed to Norway".

The diary also carries a report on Luftwaffe operations. "The morale of the flying units is excellent", it says. "These units are strained but not over-strained." It then goes on to observe that, in general, only fighter-bomber aircraft equipped with 250Kg bombs are to be committed in daylight operations against London and alternate targets. These are to fly at extremely high altitudes and, it is thought, the damages caused in London are "very considerable".

In Britain, the media focus is not on the domestic front. Big events are being staged in France where, only 24 hours after Churchill has made a radio appeal to the French to rise up and set Europe aflame.

Predictably, Göbbels is less than impressed. "Impudent, insulting, and oozing with hypocrisy", he calls it, "A repulsive, oily obscenity". He releases the speech to the [German] press for them "to give it a really rough and ready answer" Otherwise, he writes, the English will carry on living an illusion. We shall battle on remorselessly to destroy their last hopes.

This day, Hitler arrives secretly in Paris to have a long conference with Pierre Laval. Reports emerging from Berlin indicate that Hitler is offering final peace terms to France in exchange for the surrender of the remnants of the French fleet. With the help of the French, Hitler and Mussolini are said to be planning a "decisive blow against the British Fleet in the Mediterranean.

According to the Daily Express, "Jubilant Nazi officials in Berlin boast that the three navies could either destroy the British Fleet or drive it off our great Empire lifeline."

|

| A DH. 95 passenger aircraft. The Herefordshire differed from the Flamingo in having oval rather then square windows. |

Combat fliers were not the only casualties this day. On a scheduled flight to Belfast from RAF Hendon was a Hertfordshire aircraft, the militarised version of the De Haviland Flamingo passenger aircraft, and the only one of its kind. Shortly after take-off, its elevator jammed and it crashed at Mill Hill, a few miles north.

Eleven people were killed – five crew and six passengers, the latter including Air Vice Marshal Blount, a first-class cricketer and commander of the air component of the BEF in France. After the Battle of France, he had returned to England to resume his original post as AOC, No. 22 (Army Co-Operation) Group. He was three days short of his 47th birthday.

COMMENT: Battle of Britain thread

22 October, 2010

Day 105 - Battle of Britain

Today sees what can only be regarded as a "planted" story on the front page of the Daily Mirror. Too close to the convoy disasters of SC7 and HX79 to be a coincidence, without giving any details of the events, it tells of a "Big U-Boat Blitz on our ships," the lead text stating:

This is Führer Directive No. 9 writ large. It has never really gone away and now, of the three options for defeating Britain, it is the only one left. As the paper acknowledges, openly, "air attack and invasion plans have been rebuffed." The "terror" bombing has failed. That leaves the economic war - the blockade.

But, says the Mirror, Britain's food chiefs give the lie to Hitler's starvation threat. It will be averted, said Lord Woolton, Minister of Food, last week. "By the grace of God and the vigilance of the Royal Navy, the courage of the Mercantile Marine, the devotion of the dock labourers and transport workers and of food traders and the patient efforts of the farmers."

With the recent disasters yet to be released, this has every sign of a piece which has been designed to soften people up for the bad news. Soon, convoy survivors will be coming ashore and talking. Details of the sinkings cannot be concealed for ever.

COMMENT: Battle of Britain thread

Hitler has started an intensified U-boat war in the hope of starving Britain into subjection by blockade now that his air attack and invasion plans have been rebuffed. Prowling in the wastes of the Atlantic, U-boats are hunting shipping, attacking on a scale greater than ever before. Scantily armed cargo boats, carrying food, raw material and munitions are their prey.More U-boats have been ordered into the Atlantic than at any time since the outbreak of war, the paper continues. In remote shipyards in Norway and the Baltic work has been pressed forward to repair the losses inflicted on the German underwater fleet in the early stages of the war by the Royal Navy and the RAF. The new vessels have been dispatched direct from their trials with the instructions, "Britain must be blockaded at all costs. Merchant ships must be intercepted and sunk."

This is Führer Directive No. 9 writ large. It has never really gone away and now, of the three options for defeating Britain, it is the only one left. As the paper acknowledges, openly, "air attack and invasion plans have been rebuffed." The "terror" bombing has failed. That leaves the economic war - the blockade.

But, says the Mirror, Britain's food chiefs give the lie to Hitler's starvation threat. It will be averted, said Lord Woolton, Minister of Food, last week. "By the grace of God and the vigilance of the Royal Navy, the courage of the Mercantile Marine, the devotion of the dock labourers and transport workers and of food traders and the patient efforts of the farmers."

With the recent disasters yet to be released, this has every sign of a piece which has been designed to soften people up for the bad news. Soon, convoy survivors will be coming ashore and talking. Details of the sinkings cannot be concealed for ever.

COMMENT: Battle of Britain thread

21 October, 2010

Day 104 - Battle of Britain

The photograph is taken today, according to the agency file which tells you nothing more than the obvious - three survivors from a bombing raid in London. To get past the censor, there is no detail which will help pinpoint the location or anything specific about the circumstances of the incident it purports to depict. For all we know, the scene has been staged. Many were.

The previous night's flying by the Luftwaffe may well have dispossessed these ladies, but Bomber Command, too, has been particularly active. It detailed 192 aircraft for missions, of which 135 report successful attacks on targets ranging from the Channel ports, German marshalling yards, armament factories in Czechoslovakia and factories in Italy. Nine aircraft are lost.

The exercise gives the Daily Mirror its headline for the morning, which offers the legend: "RAF's 100-a-minute bombing". But less comfortable is the news that an Italian push is expected in the Western Desert - the one area in the world where there is currently direct confrontation between British and Axis ground forces.

In England during the day, there is low cloud and mist over most areas of the south-east, which persist for much of the day - indicative of the general deterioration in weather conditions which effectively rule out any idea of an invasion. There is very little flying, with the RAF losing three aircraft to accidents and none to combat.

This, once again, is regarded as a "quiet" period - but come the night, Coventry suffers heavy raids, with considerable damage done to the Armstrong-Siddeley works. There are also raids over London, Birmingham and Liverpool. To the Battle of Britain commentariat, though, the night bombing is still all but invisible. One could speculate on what might have been the response had Fighter Command been equipped with effective night fighters. One presumes the the narrative would then have been extended to cover the night.

Perhaps the most significant news, however, is a report in the Yorkshire Post, on "New Drive for Shelters". Measures announced over the week-end, it says, "suggest a determined attempt by the Government to come to grips with the shelter problem. To speed up the provision of shelters, the whole cost of building and equipment in future is to be paid by the Government so long as local authorities show reasonable economy in their schemes."

This is an important development, and is unlikely to be unrelated to the recent spate of shelter disasters. The Yorkshire Post remarks that "this is a promise that has long been needed." Much of the delay in shelter construction, it says, "has been due to uncertainty in the minds of local authorities whether they would find themselves burdened with intolerable debts if they showed initiative and went vigorously ahead with shelter construction. It is to be hoped that laggard authorities will now set to work with confidence."

COMMENT: Battle of Britain thread

20 October, 2010

Day 103 - Battle of Britain

It is now just over two weeks to the general election in the United States, upon which outcome will depend Britain's fate. If Roosevelt wins, there is a chance America will enter the war. His opponent, Wendell Wilkie is running on an isolationist ticket, which could auger ill for the UK, except that Roosevelt looks to have a two to one lead in the electoral college.

Back in the war, the Luftwaffe is continuing to pursue its daylight tactics of sending over high-level fighter bombers. Such aircraft and their escorts amount to 300 on this day, in five separate waves, keeping RAF pilots busy and tired. Fighter Command flies 745 sorties and loses four aircraft, the Luftwaffe combat losses amounting to eight, including a Do 17 on a reconnaissance flight. As always, the RAF exaggerates its score, claiming 14 aircraft downed.

Overnight, bombers revisit London. Coventry is heavily bombed and considerable damage is done. Rescue parties are heavily tested as several people are trapped in wrecked buildings. Minelayers are also active off East Anglia, and from the Humber to the Tees.

Meanwhile, British Intelligence has picked up rumours that the Vichy government is preparing its ships and colonial troops to aid the Germans in the war against the United Kingdom. Churchill is informed, but does not believe the rumours. Nevertheless, he appreciates that, if the French fleet, now at Toulon, was handed over to the Germans, it would be a very heavy blow. He writes to the US president, expressing his concerns.

Roosevelt responds in very positive fashion, warning that such an action would constitute "a flagrant and deliberate breach of faith with the United States Government". It would definitely wreck the traditional friendship between the French and the American peoples, create a wave of bitter indignation against France and permanently end all American aid to the French people. Further, there would be no US assistance when the time came to secure for France the retention of her overseas possessions.

COMMENT: Battle of Britain thread

19 October, 2010

Day 102 - Battle of Britain

The agony of Convoy SC7 continues into today. SS Empire Brigand and her load of trucks disappeares beneath the waves. Six of her crew die. Even the Commodore's ship is not immune, and SS Assyrian sinks beneath him. Vice Admiral Mackinnon is saved. SS Fiscus loaded with 5-ton ingots of steel, sinks like a stone. There is only one survivor from her crew of 39.

Twenty ships out of 34 which had remained in the convoy have now been sunk. The loss amounts to 79,592 tons, worth millions, even at 1940 prices. The German "star" is Otto Kretschmer. He operated for only 18 months of WW2 before being captured but sank 56 ships totalling 313,611 tons. This is a feat unequalled by any other U-Boat Captain. In U-99 this night, he sinks seven ships.

And still the killing has not finished. Those U-boats with torpedoes remaining join up with U-47, commanded by Gunther Prien, to attack HX79, another Liverpool-bound convoy, this one completely unescorted. A further 12 ships are sunk, with no loss to U-Boats, making this the worst loss of ships in a 48 hour period for the entire war.

Despite this, the U-boats are by no means the only weapon ranged against the Atlantic convoys. The long-range Focke-Wulf Fw 200 Condor (pictured above), first operating from Norway and later from France, is able to fly far out into the North Atlantic, out of the reach of the RAF's shore-based Spitfires and Hurricanes, and even the longer-range Blenheims.

The Condors provide detailed reports on convoy positions to waiting submarines, they send meteorological reports and mount direct attacks on the shipping with their own bombs. Between June 1940 and February 1941, this type alone accounts for sinking over 365,000 tons.

As to the fate of SC7 and HX79, it is still too early for anything of these convoy disasters to reach the media. H Taylor Henry, writing for AP, his copy to reach millions of Americans, reports on the war in London: "High explosive bombs dropped by raiders in the heaviest early-evening assault since the battle of Britain began killed many Londoners last night and caused "severe" damage in the British capital", he says. "One bomb landing outside a hotel," he adds, "killed an unannounced number of people in the bar; two others were killed in a cafe, and a direct hit which demolished a London club killed an undetermined number of casualties".

Golden prose this is not - and the details are suspect. Henry may be eliding incidents from several days into one narrative. But the report captures the flavour of events. The bloody war just got bloodier. This is corroborated by the Ministry of Homes Security activity report, which tells us that the bombing commenced at dusk and for the first four hours was abnormally heavy, then continuing on a large but more usual scale. The main attacks were against the London area, but Liverpool, Manchester and Coventry districts received considerable attention.

Reading the Daily Express, however, you would think it was a different war:

For the third Friday in succession, last night's London blitz was quieter than usual. This weekly "quiet night" has been marked by the anti aircraft gunners, who call it "Jerry's Amaminight." On each of the two previous Fridays an early "Raiders passed" was sounded. Last night's raid, which ended the blitz's sixth week, began in a blanket of mist and low-lying cloud that made it impossible to pick out targets from the air.It's how you tell 'em, I guess.

Bombs were unloaded blindly and. as on the previous night, there were long lulls. A public house was blown into the roadway, and people were buried under the wreckage. A cafe and a shop were demolished by the same bomb. Close by, incendiaries fell on a hospital, but were quickly put out.

The main news, however, is an account culled from US newspapers of how aircraft from Bomber Command under their former leader Charles Portal, assisted had in mid-September pounded the assembled German invasion fleet so hard - killing 40-50,000 troops - that it had forced the cancellation of Der Tag - the projected invasion day.

Although Bomber Command had indeed mounted a "maximum effort" on the night of 15 September, and again on the 17th, the account is almost entirely fictional. Despite this, it is, according to the Express, "officially confirmed". The Air Ministry is thus crediting Bomber Command rather than Dowding's Fighter Command with the victory. - a victory which, according to the legend, is the reason why Portal has been promoted to Air Force Chief of Staff.

How times change. With the Battle of Britain "brand" having become the exclusive property of Fighter Command, bomber crews are not even awarded the Battle of Britain clasp.

COMMENT: Battle of Britain thread

18 October, 2010

Day 101 - Battle of Britain

Unknown at the time, and only to be discovered after the war when German war records are translated, the war against Britain in 1940 has been initiated by Führer Directive 16, since postponed, but also the earlier Directive No. 9. That this is still in force is seen most immediately by the thirty-five merchantmen making up Convoy SC7, outbound from Nova Scotia since 5 October.

They were headed for Liverpool, escorted by a single Royal Navy Warship, the sloop HMS Scarborough. Leading the convoy in the small 2,962 ton SS Assyrian, Vice Admiral L.D.I. Mackinnon, a retired Naval Officer, acting as convoy Commodore. Typical cargoes carried show the range of goods that Britain most needs to import to sustain her. Pit props from East Brunswick destined for British coal mines, lumber, and grain for the daily bread of the English population from the Great Lakes area, steel and ingots ex Sydney Cape Breton, iron ore from New Foundland.

The largest of the 34 ships was the Admiralty tanker SS Languedor of 9,512 tons - already sunk yesterday, and a load of important trucks fills the holds of SS Empire Brigand. The majority of the ships belong on the British Register, but others have their home ports in Norway, Greece, Holland, and Sweden.

The attacks actually started in the early hours of 16 October, when one ship was lost, but the convoy is then joined by the sloop Fowey and corvette Bluebell. On the 18th, two further escorts join the convoy, the sloop Leith and corvette Heartsease. That night, the convoy is under sustained attack from one of the first German U-boat "wolfpacks", with seven submarines coordinating their attacks.

One, the SS Creekirk (3,917grt) with a cargo of iron ore (pictured), is hit by torpedoes from U-101 early in the attack. Weighted by the iron ore, she sinks almost immediately, with the loss of her master, Elie Robilliard, 34 crew members and one gunner. No one survives.

The disaster is not yet played out and little enough is to filter into the media, and then not for some little time. But it says something of the the importance to Britain of sea warfare that the appointment of a new C-in-C to the Home Fleet gets star billing on the front page of the Daily Express and many other newspapers of the day. Novelty wins out with the second lead, giving the Dean of Canterbury high profile as his house is bombed for the second time.

In the end, that is what it comes to. Even the horrific becomes so routine that it gets a one-column "round-up" article. In peacetime, any one of the hundreds of incidents would have merited front-page treatment on their own. Not any more - wartime has deadened the sensibilities and re-ordered the hierarchy of death.

During the day, the Luftwaffe is back, its aircrew fortified by an Order of the Day from Göring, who tells them: "German airmen, comrades! You have, above all in the last few days and nights, caused the British world-enemy disastrous losses by uninterrupted, destructive blows. Your indefatigable, courageous attacks on the heart of the British Empire, the city of London with its 8½ million inhabitants, have reduced British plutocracy to fear and terror. The losses which you have inflicted on the much vaunted Royal Air Force in determined fighter engagements are irreplaceable."

The Luftwaffe "celebrates" by mounting four fighter sweeps over Kent, some reaching the London district and the Thames Estuary. Approximately 300 fighter aircraft are deployed, some of which carry bombs. Four are claimed downed, while Fighter Command loses three aircraft with three pilots killed or missing.

One needs to be reminded that London is not the only recipient of German largesse. This night, as with many before, Birmingham takes the strain. The air raid warning sounds at 19.47hrs and the first bomb drops just over 15 minutes later. By the time the "all clear" comes at 23.29hrs, approximately 116 HE bombs have dropped, 34 of which do not explode. About 107 incidents involve incendiaries and about 78 fires are started.

The districts most affected are Sparkbrook, Sparkhill, Balsall Heath, Duddeston and Aston - names which are meaningless to most outside the area. Slight damage is caused to a number of factories, production is interrupted in a number of others because of the unexploded bombs, and there are some shops damaged. Trains are delayed on the main LMS Birmingham to London line, after a bomb damages an embankment. Other damage included the local gas works and a local canal.

But for all that, the total casualties were ten fatalities and 18 injured. But, over term, Birmingham is the third most heavily bombed UK city during the war, behind London and Liverpool. During the Blitz 2,241 people are killed, and 3,010 seriously injured. A total of 12,391 houses, 302 factories and 239 other buildings are destroyed, with many more damaged. Overall, around 2,000 tons of bombs are dropped on Birmingham during the conflict.

Yesterday, it was much the same. The siren sounded at 19:57 hrs and started falling at 20:05hrs. The "all clear" sounds at 21.35hrs. That time, approximately 117 HE bombs are dropped, and 41 do not explode. There were 95 incendiary bomb incidents.

The districts most affected represent another litany of unknown places: Sparkhill, Sparkbrook, Small Heath, Saltley, Bordesley Green and Erdington. Many houses were damaged in these areas and the total casualties run to 17 dead and 14 injured. Nine of those are killed and six are injured in one street as when an HE bomb demolishes a group of houses. A family of twelve is trapped in one of the houses.

A long list of domestic, commercial and industrial premises damaged marks another raid. The Brummies dust themselves off, bury their dead, treat their injured and repair the damage. The chief fire officer and already resigned. He was useless and has been replaced.

The rescue services now work tolerably well, and their members too are taking casualties. Two Police Constables are overcome by coal gas fumes as they go to the aid of the stricken in one incident. A fireman is killed and three badly injured were an HE bomb demolishes Small Heath Motors Garage, an AFS (Auxiliary Fire Service) Station.

That is the nature of attrition. And tragically, on this day, the slaughter is not confined to the Midlands. London is also on the receiving end, as it has been for so many nights. Iin Lambeth, the Rose and Crown Public House is completely demolished at 20:25hrs by a direct hit. Over 40 are killed.

COMMENT: Battle of Britain thread

17 October, 2010

Day 100 - Battle of Britain

This week's edition of the specialist aviation magazine Flight is published today, and in its leader and a long review of the "War in the Air", it offers a series of insights which possibly hold the clue into the thinking which drives the Battle of Britain legend.

Oddly, for an aviation magazine, the front cover has an advert which depicts a motor torpedo boat engaged in a fleet action - but this is possibly explained by the fact that the manufacturer, the British Power Boat Company, also produces seaplane tenders and rescue launches for the RAF. The investment of a cover ad suggests that there might be business in the offing - the RAF looking to order some air-sea rescue launches perhaps.

That aside, the magazine's offerings must be taken in reverse order, to get the full flavour, starting with its analysis of the war in the air. In this, it notes that the Germans have lately been "largely employing" Me 109s fighters converted into bombers, which is indeed the case - but the "conventional" bomber force is still actively deployed on night missions.

The leader, however, does not refer to this. Rather, it suggests that the use of Me 109 fighter bombers "indicates that the Germans have admitted to themselves that the attempt to overwhelm Britain from the air has failed." It then concludes that:

But the clue to the reason behind this thinking is in the leader. Doffing its cap to the recent damage done by the night bombing, it goes on to declare:

But the Luftwaffe, having failed to prevail over the RAF in the light of day, has bypassed it and is by night attacking the population directly, seeking a resolution by means other than armed warriors prevailing over another set of armed warriors. This idea, it seems, Flight magazine - and the military in general (or, most certainly, the RAF) - cannot cope with. A battle between the military of one nation, on the one hand, and the people of another, does not count as a "proper" battle. So it is ignored. The people in the shelters do not count.

Yet, in the week up to today, German bombing has killed 1,567 people, nearly three times the number of Fighter Command aircrew killed in the entire Battle of Britain period. And, unlike the memorials so carefully tended, the names of the airmen so assiduously recorded, for many of the "unknown soldiers" of this conflict, there is no marked grave, no memorial. And many are killed in the line of duty. This day, in Streatham, at approximately 21:35hrs a direct hit is registered on the fire station. Two heavy appliances are wrecked. Twelve firemen are killed and eight are injured.

Even then, there is another huge "elephant in the room" - the sea war. And while a specialist aviation magazine might not be expected to take a broader view of the conflict, there is little excuse for historians who take the "Battle of Britain" at face value or, more specifically, the value attributed to it by Fighter Command.

But early on this day, the Kriegsmarine destroyer flotilla based in Brest is out hunting. Comprising once more destroyers Steinbrinck, Lody, Ihn and Galster, it is joined by six torpedo boats out of Cherbourg, intent raiding British shipping at the western exit of the Bristol Channel.

Three convoys are in grave danger but, fortunately, the destroyers are sighted at 07:19hrs by aircraft of Coastal Command, shortly after they have left Brest. The convoys are ordered to steer west until the threat is dealt with. Light cruisers Newcastle and Emerald, with five destroyers race out of Plymouth at 11:00hrs and, five hours later, have sighted the German force.

At distance, gunfire is exchanged but the Germans do not close for battle. They pull clear and disengage by 18:00hrs, turning for home. They are pursued by Blenheim bombers of No. 59 Sqn, one of which fails to return. All three crew are killed, the only casualties of the action.

Compared with the huge publicity afforded to Fighter Command, the activities of which are emblazoned on newspaper sellers' boards before even the fighter engines have cooled, this successful action gets a grudging mention, down page in the Daily Express two days later, and the back page of the Daily Mirror.

And yet, this is only a tiny fraction of the war at sea this day, a war which is never give the "star treatment" afforded to the fighters. As they do virtually every day of this long war, the coastal convoys are on the move, OB.230 departing Liverpool escorted by destroyers Antelope and Clare, corvettes Anemone, Clematis, Mallow, and anti-submarine trawlers St Loman and St Zeno.

Coastal convoy FN.311 departs Southend, escorted by destroyers Verdun and Watchman, headed north, while convoy FS.312 at the other end of the chain starts is southward journey, escorted by destroyers Wallace and Westminster. Anti-aircraft cruiser Curacoa transferred to convoy SL.49 A east of Pentland Firth and escorted it towards Buchanness, then joining convoy EN.10.

For the German U-Boats, the period July to October - right through the Battle of Britain - is called the "happy time" by commanders. In these four months, 144 unescorted and 73 escorted ships are sunk, with only six U-boats destroyed by British forces - of which only two are destroyed by attacks on convoys. And October is shaping up to be the worst month of them all for allied shipping.

On this day, U-38 sinks Greek steamer Aemos (3554grt), a straggler due to bad weather from convoy SC.7. Four crew are lost. U-48 attacks on convoy SC.7, sinking British tanker Languedoc (9512grt) and steamer Scoresby (3843grt). It damages steamer Haspenden (4678grt). U-93 attacks convoy OB.228 and sinks Norwegian steamer Dokka (1168grt) and British steamer Uskbridge (2715grt). Ten crew are lost on the Norwegian steamer, two on the British ship.

Then there are the mines. The British steamer Frankrig (1361grt) is mined in the North Sea. Nineteen crew are rescued. British fishing vessel Albatross is sunk by a mine off Grimsby. All but five crew are lost. Faroes motor fishing vessel Cheerful is sunk on a mine off the Faroes Island. British steamer Ethylene (936grt) is damaged on a mine close to the East Oaze Light Buoy. British steamer George Balfour (1570grt) is damaged on a mine eight miles from the Aldeburgh Light Vessel.

Six miles north, northwest of Smith's Knoll, British steamer Hauxley (1595grt) in convoy FN.311 is torpedoed by German motor torpedo boat She sinks under tow of Destroyer Worcester at 06:45hrs on the 18th. One crew is lost on the British steamer. British steamers P L M. 14 (3754grt) and Gasfire (2972grt) in the same convoy are damaged by German motor torpedo boats British steamer Brian (1074grt) claims sinking one of the German S-boats.

Only a fraction of this is to reach the media, yet the human energy expended far exceeds that devoted to the air war. And, while the fighting over the skies of Britain has descended into a meaningless scrap, of no strategic importance, upon the sea battle - in its totality - depends the very survival of Britain.

(Inquiry into daytime tactics)

COMMENT: Battle of Britain thread

Oddly, for an aviation magazine, the front cover has an advert which depicts a motor torpedo boat engaged in a fleet action - but this is possibly explained by the fact that the manufacturer, the British Power Boat Company, also produces seaplane tenders and rescue launches for the RAF. The investment of a cover ad suggests that there might be business in the offing - the RAF looking to order some air-sea rescue launches perhaps.

That aside, the magazine's offerings must be taken in reverse order, to get the full flavour, starting with its analysis of the war in the air. In this, it notes that the Germans have lately been "largely employing" Me 109s fighters converted into bombers, which is indeed the case - but the "conventional" bomber force is still actively deployed on night missions.

The leader, however, does not refer to this. Rather, it suggests that the use of Me 109 fighter bombers "indicates that the Germans have admitted to themselves that the attempt to overwhelm Britain from the air has failed." It then concludes that:

If the next great compaign (sic) is to be staged in the Balkans, or if bomber reinforcements are to be sent by Germany to the help of the Italian forces in Africa, there is good reason for conserving the German heavy bombers, which may be gradually withdrawn to the other spheres. That is one reading of the present position, and events should soon show whether it is correct.Curiously, the analysis here is being based on developments in the day fighting, almost as if the night bombing does not exist. Yet the reality is that the Germans have changed tactics, following the British in confining their heavy bomber fleet to night operations, while harassing the RAF during the day with raids by fighter bombers (a tactic which is giving 11 Group some considerable grief). That the night bombing had just been ramped up to a new peak of intensity and savagery is hardly indicative of the Germans having admitted failure.

But the clue to the reason behind this thinking is in the leader. Doffing its cap to the recent damage done by the night bombing, it goes on to declare:

We suffer indeed, but such sufferings do not affect our power to carry on the war, and indignation at the tragedies makes the British people all the more grimly determined that this barbarism must be stamped out of the world. From the military point of view, the Battle of Britain is going well for the enemies of the Axis.For all its brave discussions in past editions about total war, Douhet's theorising and the rest, the magazine (or its editorial team) is still looking at the conflict as one fought between military forces. And, in the sense that the RAF has confronted the Luftwaffe in the daylight battle and "won" means, in those terms, that the "Battle of Britain" - defined as a military conflict between the two air forces - is indeed going well.

But the Luftwaffe, having failed to prevail over the RAF in the light of day, has bypassed it and is by night attacking the population directly, seeking a resolution by means other than armed warriors prevailing over another set of armed warriors. This idea, it seems, Flight magazine - and the military in general (or, most certainly, the RAF) - cannot cope with. A battle between the military of one nation, on the one hand, and the people of another, does not count as a "proper" battle. So it is ignored. The people in the shelters do not count.

Yet, in the week up to today, German bombing has killed 1,567 people, nearly three times the number of Fighter Command aircrew killed in the entire Battle of Britain period. And, unlike the memorials so carefully tended, the names of the airmen so assiduously recorded, for many of the "unknown soldiers" of this conflict, there is no marked grave, no memorial. And many are killed in the line of duty. This day, in Streatham, at approximately 21:35hrs a direct hit is registered on the fire station. Two heavy appliances are wrecked. Twelve firemen are killed and eight are injured.

Even then, there is another huge "elephant in the room" - the sea war. And while a specialist aviation magazine might not be expected to take a broader view of the conflict, there is little excuse for historians who take the "Battle of Britain" at face value or, more specifically, the value attributed to it by Fighter Command.

But early on this day, the Kriegsmarine destroyer flotilla based in Brest is out hunting. Comprising once more destroyers Steinbrinck, Lody, Ihn and Galster, it is joined by six torpedo boats out of Cherbourg, intent raiding British shipping at the western exit of the Bristol Channel.

Three convoys are in grave danger but, fortunately, the destroyers are sighted at 07:19hrs by aircraft of Coastal Command, shortly after they have left Brest. The convoys are ordered to steer west until the threat is dealt with. Light cruisers Newcastle and Emerald, with five destroyers race out of Plymouth at 11:00hrs and, five hours later, have sighted the German force.

At distance, gunfire is exchanged but the Germans do not close for battle. They pull clear and disengage by 18:00hrs, turning for home. They are pursued by Blenheim bombers of No. 59 Sqn, one of which fails to return. All three crew are killed, the only casualties of the action.

Compared with the huge publicity afforded to Fighter Command, the activities of which are emblazoned on newspaper sellers' boards before even the fighter engines have cooled, this successful action gets a grudging mention, down page in the Daily Express two days later, and the back page of the Daily Mirror.

And yet, this is only a tiny fraction of the war at sea this day, a war which is never give the "star treatment" afforded to the fighters. As they do virtually every day of this long war, the coastal convoys are on the move, OB.230 departing Liverpool escorted by destroyers Antelope and Clare, corvettes Anemone, Clematis, Mallow, and anti-submarine trawlers St Loman and St Zeno.

Coastal convoy FN.311 departs Southend, escorted by destroyers Verdun and Watchman, headed north, while convoy FS.312 at the other end of the chain starts is southward journey, escorted by destroyers Wallace and Westminster. Anti-aircraft cruiser Curacoa transferred to convoy SL.49 A east of Pentland Firth and escorted it towards Buchanness, then joining convoy EN.10.

For the German U-Boats, the period July to October - right through the Battle of Britain - is called the "happy time" by commanders. In these four months, 144 unescorted and 73 escorted ships are sunk, with only six U-boats destroyed by British forces - of which only two are destroyed by attacks on convoys. And October is shaping up to be the worst month of them all for allied shipping.

On this day, U-38 sinks Greek steamer Aemos (3554grt), a straggler due to bad weather from convoy SC.7. Four crew are lost. U-48 attacks on convoy SC.7, sinking British tanker Languedoc (9512grt) and steamer Scoresby (3843grt). It damages steamer Haspenden (4678grt). U-93 attacks convoy OB.228 and sinks Norwegian steamer Dokka (1168grt) and British steamer Uskbridge (2715grt). Ten crew are lost on the Norwegian steamer, two on the British ship.

Then there are the mines. The British steamer Frankrig (1361grt) is mined in the North Sea. Nineteen crew are rescued. British fishing vessel Albatross is sunk by a mine off Grimsby. All but five crew are lost. Faroes motor fishing vessel Cheerful is sunk on a mine off the Faroes Island. British steamer Ethylene (936grt) is damaged on a mine close to the East Oaze Light Buoy. British steamer George Balfour (1570grt) is damaged on a mine eight miles from the Aldeburgh Light Vessel.