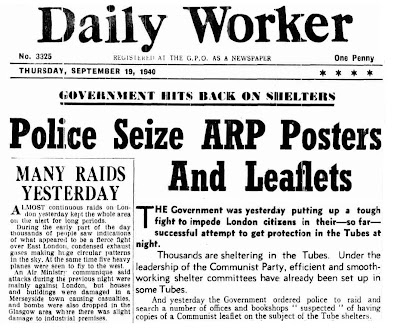

In response to the Communist campaign for better shelters, the Police had now taken action. In an open attempt to suppress dissent, they had been ordered to raid and search a number of offices and bookshops "suspected" of having copies of a Communist leaflet on the subject of the Tube shelters. According to the Daily Worker, on the day previously day, "plain clothes police swarmed about these places. Into one office they burst their way with violence, refusing to show search warrants until the search was completed".

Railway workers, by then, were actively colluding with the Communist Party, allowing people to take cover in the Tubes during raids. But at Warren Street - despite the apparent relaxation by the Police Commissioner - police had intervened after some had been allowed into the station, leaving 150 stranded when the gates were locked. Only when a man with a crowbar threatened to smash the gates had the Police relented, and the people had been allowed admission.

At Goodge Street tube station, Police had tried to form a barricade to prevent anyone entering during a raid. But, during a burst of "particularly fierce" anti-aircraft gunfire, the crowd had swept forward and brushed the police aside.

Such events would have passed by Gen. Alan Brooke. That morning he had been on his way to Hendon where the military executive aircraft were based, and later complained of the difficulties in getting out of town. Most roads were closed, including Piccadilly, Regent St, Bond St and Park Lane. There were big craters around Marble Arch. That evening, on his return to London, a heavy bomb shook the club building in which he was staying.

Some of the misery was thus being shared, the effects of which were as significant as the bombs on Buckingham Palace. A potential stress point was becoming a unifying force. And the “survivors” of Buckingham Palace were out and about, among the people.

Guided by Ministry of Information officials, the King and Queen were taken to see survivors of "heroic rescues", throughout a tour of three districts of London which had sustained extensive bomb damage. A special point was made of introducing the royal couple to men and women whose houses had been wrecked by a direct hit. As he had on 9 September, the King once again talked up the Anderson shelters, this time saying: "These Anderson shelters are wonderful". The King and Queen "listened with interest" while occupants of two unharmed shelters told them of escapes when the bomb fell only a few yards away.

With unconscious irony, the regional Yorkshire Post illustrated precisely the contradictions at the heart of media reporting. On the one hand, there was the lead story proclaiming: "Another RAF triumph". Next, there was the story declaring: "Smashing blows at invasion plans", an account of yet more attacks on invasion ports. Then, centre page, was pictured the devastation at the very heart of the West End, testimony to the RAF's failure to deny the night sky to the Luftwaffe.

Nevertheless, the Daily Mirror picked up on Sinclair's speech of the previous day, headlining: "Bombing of London by night is not an insoluble problem. We are making progress".

Later that day, Nicolson noted in his diary that, "unless we can invent an antidote to night-bombing, London will suffer very severely and the spirit of our people may be broken". Already the Communists were getting people in shelters to sign a peace petition to Churchill, he wrote. "One cannot expect the population of a great city to sit up all night in shelters week after week without losing their spirit".

The AP was almost poetic about the overnight raid. "Battered, grimy London took its 13th straight day of devastating bomb assault today, shook off the horrors of the war's worst night and dealt staunchly with the prospect of spending a winter underground,” it recorded. The Australian Associated Press was of the same mind: "Many observers regard last night's raid on London as the most savage yet". It went on to say: "The Germans flew lower than ever previously, and took suicidal chances as they frenziedly endeavoured to pierce the hellish curtain of fire around and over London". The raiders made no effort to seek out military objectives.

Despite this, the Manchester Guardian led on the anti-invasion campaign – conveying the upbeat message that the RAF was on the ball, dealing expeditiously and effectively with the "most serious threat on the horizon". It retailed claims of the RAF having caused "heavy damage", but for once these were not without foundation. The OKW War Diary recorded eighty barges having been sunk,

Despite this, the Manchester Guardian led on the anti-invasion campaign – conveying the upbeat message that the RAF was on the ball, dealing expeditiously and effectively with the "most serious threat on the horizon". It retailed claims of the RAF having caused "heavy damage", but for once these were not without foundation. The OKW War Diary recorded eighty barges having been sunk,and an ammunition train with 500 tons of explosives blown up. It also reported a torpedo boat sunk and one damaged.

The Daily Mail, on the other hand, focused on the domestic situation, catching up with the Daily Worker. It too was now launching a vigorous campaign for improved air-raid shelters and better arrangements for the daily lives of the ten million residents of the Greater London area.

The paper noted that the government had become aware that Underground stations were being used as shelters but declared: "something much better must be devised". It added: "no question of cost should be allowed to hold up construction". It then blamed the "reluctance to provide such quarters" on the government of the former Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain and its "cheeseparing policy". The present shelter policy had been "proven by experience to be wrong".

Joining in the criticism, the Mirror slammed "those unimaginative bodies or persons known as the authorities" for rejecting deep shelters and then for failing to devise a new policy. It does seem odd, the paper said, that even now, in the midst of the air war, learned persons should still be considering, inquiring, investigating and making notes.

On the other hand, Beaverbrook's Express had on its front page a piece recording: "Don't use tubes as shelters" – a joint appeal by the Ministries of Security and Transport, "to the good sense of the public, and particularly to able-bodied men, to refrain from using Tube stations as air raid shelters except in case of urgent necessity". It was immediately followed by another piece headed: "But they did".

Thousands of Londoners again had taken three-halfpenny tickets on the Underground last night – to sleep on the station platforms. At most stations there were police in attendance to shepherd them gently to leave free passage for passengers on the trains. "The whole position is under review,” said an official of the London Passenger Transport Board. "At the moment we are taking no action providing services are not interfered with and fare paying passengers are not impeded".

This was not good enough for the newspaper, which headed its editorial: "Hold fast". Addressing what it felt to be a defeatist sentiment, it spoke to the whole city:

The Daily Express makes this appeal to the people of London, many of them homeless, many of them in nightly fear of being made so. On your courage and discipline much depends. You are asked to show unparalleled fortitude in face of this great menace. Life is held cheap by our enemies and they seek to disrupt you physically and mentally. If you hold on, behaving with the bearing of soldiers, obeying the instructions you are given, then liberty will one day be yours again. But if you give way then you face the prospect of a lifetime of misery and torture under a foreign heel.

It looked as if the government was going to make a stand. The Press Association reported that the prime minister and government were convinced that "deep or heavily protected" shelters were impossible to construct in wartime and that the job would be "more or less impracticable" even in peacetime. Anderson complained in the House of Commons of people being misled into believing such shelters were safer.

It looked as if the government was going to make a stand. The Press Association reported that the prime minister and government were convinced that "deep or heavily protected" shelters were impossible to construct in wartime and that the job would be "more or less impracticable" even in peacetime. Anderson complained in the House of Commons of people being misled into believing such shelters were safer.That evening, William Mabane, Anderson's parliamentary secretary, broadcast on the BBC. He urged the public not to leave their Anderson shelters for public shelters, saying it deprived others of shelter. "We're going to improve the amenities in existing shelters", he promised. "We're setting about providing better lighting and better accommodation for sleeping and better sanitary arrangements".

But discord could not be contained. The story even reached the New York Times. In a "special cable", its correspondent wrote of the Commons going into secret session to discuss the mounting housing crisis, the absence of suitable deep shelters and the failure to take care of citizens bombed out of their homes. People had been kept in rest centres "for several days" without hot food while officials tried to arrange transportation.

Strain on the political consensus was showing. "Laborites" had co-operated with the government in maintaining this "people's war", said the NYT, but many now pointed out that the victims are not being cared for well enough. The people would put up with the hardship of this total war, but only if they were convinced the government was doing everything it could, first to guarantee their security and, second, to care for them and their families if they were bombed.

Strain on the political consensus was showing. "Laborites" had co-operated with the government in maintaining this "people's war", said the NYT, but many now pointed out that the victims are not being cared for well enough. The people would put up with the hardship of this total war, but only if they were convinced the government was doing everything it could, first to guarantee their security and, second, to care for them and their families if they were bombed.In response to the government’s appeal, the paper noted that "crowds crushing into subways indicate the growing demand for security". And in what must have been a worrying development for the government, even Home Intelligence was deserting them. "People are not so cheerful today", it reported. "There is more grumbling. Elation over the barrage is not so strong: people wonder why it is not more effective in preventing night bombing". Among the many points of tension identified, "determination of the public to use underground stations as shelters" was listed.

This was becoming a trial of strength and the government was close to losing. But there was no evidence that Churchill was engaging in the issue. Colville noted:

The PM is sufficiently undismayed by the air raids to take note of trivialities. Yesterday he sent the following note: "The First Sea Lord. Surely you can run to a new Admiralty flag. It grieves me to see the present dingy object every morning. WSC".But the tide seemed to be turning. The late edition of the Evening Standard reported that the Ministries of Transport and Home Security were examining police reports, and the reports of their own observers on the use of Tubes as dormitories. With no reference to the Warren Street of Goodge Street incidents, it was "understood" that these stated that there had been "no trouble of any kind" the previous night.

The paper further "understood" that: "there will be no question of banning the tubes for use as dormitories. Sleepers will be allowed to continue using them unofficially, but in controlled numbers".

As to air operations on the day, these had been much reduced by frontal-driven rain. Fighter Command escaped loss, and only one Blenheim was downed, against eight aircraft lost by the Luftwaffe. And in Berlin, with no fanfare, the process of dismantling Sealion was proceeding. Hitler had agreed that the notification time for assembling the fleet could be extended from ten to fifteen days, allowing some vessels to be put back into commercial use.

With that came the release of the ships held for Operation Herbstreise (Autumn Journey). This was a deception operation to be mounted from Norway. Two days prior to the actual landings, three light cruisers and the gunnery training ship Bremse and other light naval forces were to have escorted the liners Europa, Bremen, Gneisenau and Potsdam, with ten transport steamers, towards the east coast of England between Aberdeen and Newcastle, simulating a landing in the north.

Yet, in sunny Rome, Italian Foreign Minister Ciano was meeting his German counterpart, von Ribbentrop. He told Ciano that bad weather, and especially the clouds, had even more than the RAF prevented the success of the plan. The invasion would take place anyway, as soon as there were a few days of fine weather. "The landing is ready and possible. English territorial defence is non-existent. A single German division will suffice to bring about a complete collapse", he said.

COMMENT: Battle of Britain thread